For a long time I was too busy to learn anything much new, while running a company and caring for two small children. But more recently, I had the time to catch up on some technical knowledge and I remembered how much I love pure learning.

This post seems to be a big list of what I’ve learned over the last couple of years. Actually, I meant to write it a year ago, so now it’s also a list of what I need to revise.

C++

I caught up with the C++ renaissance by reading Effective Modern C++. and watching heaps of CppCon, C++Now, and Meeting C++ conference videos, such as CppCon 2014: Herb Sutter’s Back to the Basics: Essentials of Modern C++ Style, (the one with almost always auto).

I exercised my growing knowledge of modern C++ by first using some modern C++ in gtkmm and Glom, and then doing a massive rewrite of libsigc++. I also explored some modern C++ generic programming techniques with tuples and dynamic programming.

Along the way I experimented, in Glom’s code, with some of the ideas from Sean Parent’s talks, such as the “no naked for loops” idea from his “C++ Seasoning” talk from Going Native 2013.

I read the old Boost Graph Library (BGL) book, to tie C++ and graph theory together in my head. I spent lots of time, off and on, trying to clean the BGL code up, and modernize it, but it’s a struggle and I’ve only managed to get some simple stuff accepted so far.

The BGL book is ancient but its ideas about C++ concepts are only just about to become mainstream, hopefully in C++20. I also read Alexander Stepanov’s wonderful From Mathematics to Generic Programming book, which convinced me even more.

I tried to get a simple explicit operator bool check into clang-tidy itself, but that didn’t get far and I chose not to be a pain by being pushy about such an unimportant contribution.

I started to learn about some compiler theory by writing some actual code.

I listened to the complete backlog of CppCast podcast episodes and I now listen to every episode as soon as its published.

Java and Android

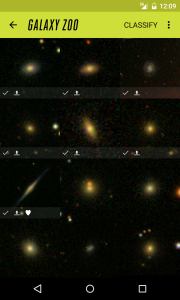

I revised and updated my Java skills by reading Effective Java Programming and Programming Android. I regularly listened to the Fragmented and Android Backstage podcasts, but not so much recently. I gained some real-world Android programming experience by creating the Android app for Galaxy Zoo after first trying to create an Android app for my Glom database system. The Galaxy Zoo app was quite popular, but sadly, it’s not working right now – I need to find time to adapt it to their changed backend API.

Java and web

I spent some time with Java as a way to work on backend (distributed) systems, reading the JAX-RS book, the,Spring Microservices in action book, and the Spring in Action book.

I gained some more Java/GWT/AppEngine (and Resty-GWT) experience by creating the Big-O Quiz website. I used bigoquiz.com to take organized notes about the computer science that I learned subsequently. It asks me questions to remind me. But see below about me rewriting bigoquiz.com with Go and Angular.

iOS / Objective-C

I learned iOS (iPhone/iPad) programming by watching all 18 lectures in Stanford’s “Developing iOS 7 Apps for iPhone and iPad” course and then creating the iOS app for Galaxy Zoo. I used Objective-C, but now I have a reason to learn Swift.

Like the Android app, this is currently broken, because the backend server now has a very different API.

Go

I learned Go via the The Go Programming Language book, taking extensive notes from the perspective of a C++ developer. To gain initial experience, I rewrote bigoquiz.com‘s backend with Go, instead of Java, and found the resulting code refreshingly simple.

I now use Go regularly at work for backend microservices and I’m quite content with it. For larger projects I’d still prefer C++, but not all projects need to be large.

Angular

I finally gave up on GWT, long after everyone else realised that it’s barely maintained. So I took the opportunity to rewrite the bigoquiz.com frontend in Angular, using Typescript. Learning it was easy with the excellent Angular tutorial.

I’ve since tried out React too.

Scala

I read the huge Programming in Scala book, because I use Scala on a large project at work. I’m fond of it, but I think its simplest ideas should just be in Java, and the cleverest stuff tends to make code hard to read.

Algorithms and Data Structures

I grew to love computer science by doing Coursera’s/Stanford’s “Algorithms: Design and Analysis” course, part 1 and part 2 by Tim Roughgarden. I then read Cracking The Coding Interview, The Algorithm Design Manual, Algorithms, by Robert Sedgewick, and the first half of the CLRS Introduction to Algorithms book. I worked through the first few lectures of Tim Roughgarden’s “A second course in Algorithms” to cover max-flow and min-cost matching algorithms.

I went through the material 2 or 3 times, from various perspectives, eventually making sure to actually implement each data structure and algorithm.

I also read Jon Bentley’s Programming Pearls book, for some practical advice.

I watched, and re-watched, far too many of Tushar Roy’s algorithm walkthrough videos.

Linux

I already have years of Linux development experience, but I knew I was missing out on some knowledge and habits. So I solidified my Linux knowledge by reading Linux System Programming. (And now, later, I think I should read it again, though I wish there was a newer edition.)

I’m still looking for a really good book about bash scripting and general command line cleverness.

Distributed Systems

I didn’t have practical experience with at-scale server-based systems but I became acquainted with the ideas by reading Google’s Site Reliability Engineering book.

I discovered it later, but Tim Berglund’s 4-hour Distributed Systems in One Lesson series of videos is an excellent and engaging overview of the main themes. If it’s no longer available on YouTube but I think it’s so good that you should buy it.

Mikito Takada’s free Distributed Systems For Fun and Profit book is also an excellent introduction and overview.

I also listened to many old episodes of the Software Engineering Radio podcast and the Software Engineering Daily podcast, which often cover similar topics.

Performance

Even as a regular C and C++ coder, I realized how little I thought about the computer architecture that my code is running on. Various talks by Andrei Alexandrescu and Chandler Carruth really opened my eyes to these performance considerations that seem more relevant in at-scale server code than they were in typical desktop applications or even in embedded code.

For instance, Andrei Alexandrescu’s Code Dive 2015 “Writing Fast Code: part 1” and part 2 talks, as well as his “Optimization Tips – Mo’ Hustle Mo’ Problems” talk at CppCon 2014 and his “Writing Quick Code in C++, Quickly” talk from Going Native 2013.

For instance, Chandler Carruth’s “Understanding Compiler Optimization” talk from Meeting C++ 2015, his “Tuning C++: Benchmarks, and CPUs and Compilers! Oh My!” talk from CppCon 2015, his “Efficiency with Algorithms, Performance with Data Structures” talk from CppCon 2014, and his “Care and Feeding of C++’s Dragons” talk from Going Native 2013. Also his more recent “High Performance Code 201: Hybid Data Structures” from CppCon 2016.

Mike Acton’s famous “Data-Oriented Design and C++” talk, from CppCon 2014, really gets to the point about this too, from more of a C perspective.

Coding Habits

I finally took the time to learn Vim enough to use it as my daily editor, after reading Practical Vim. I also learned to use screen and Tux but I haven’t incorporated either into my daily habits.

Ironically I never found my Linux environment outside of the terminal to be as keyboard friendly as the old pre-X MacOS. So staying in the terminal helped me to keep my hands off the mouse again. I practiced with the Klavaro typing tutor to get some of my good habits back.

I worked through the first 25 tasks from Project Euler and most of the tasks from HackerRank. I spent two intensive months working through every task on InterviewBit (around 260 at the time).

I highly recommend InterviewBit – they have a vast set of coding problems, nicely organised, with helpful test cases and tips for when you get stuck, so you can actually improve. HackerRank is useful too, but it feels less directed and the need to parse stdin input for every task gets annoying.

Along the way, I took a note of each C++ typo or generic algorithm mistake that I made, and started counting how many times I made each mistake, so I could focus on breaking my worst habits.

Management

I read some books about project and people management too, revising agile processes with the Scrum and XP from the Trenches and Kanban and Scrum: Making the most of both free ebooks.

The Manager’s Path maps out the various roles that are popular at software companies today, with suggestions about regular actions that each might perform, but it doesn’t seem useful beyond establishing that common language, and I hope it becomes outdated.

I recently read Measure What Matters, and Radical Focus, about OKRs, and I’m very enthusiastic so far. I like the idea of openness and regularity in businesses, to allow focus and alignment, almost like well-functioning decentralized open source projects that I’ve known.

I also got interested in product management, but I haven’t taken it far yet. The Cracking the Product Manager Interview book was rather superficial. I hope to dig deeper into this topic in future.

Others

I revised my Design Patterns knowledge by reading Head First Design Patterns and I used it to build a Design Patterns quiz.

I learned the Lua programming language and the Moai game-development platform via the Programming in Lua book and the “Developing Mobile Games with Moai SDK” book. This was for an idea I’d had for a kids’ programming app that didn’t seem quite worth the effort in the end.

I learned a bit about Hadoop by reading the “definitive guide” book, but I never got around to using it.